Nobody Checks on Divorced Dads: The Grief of Becoming a Weekend Father

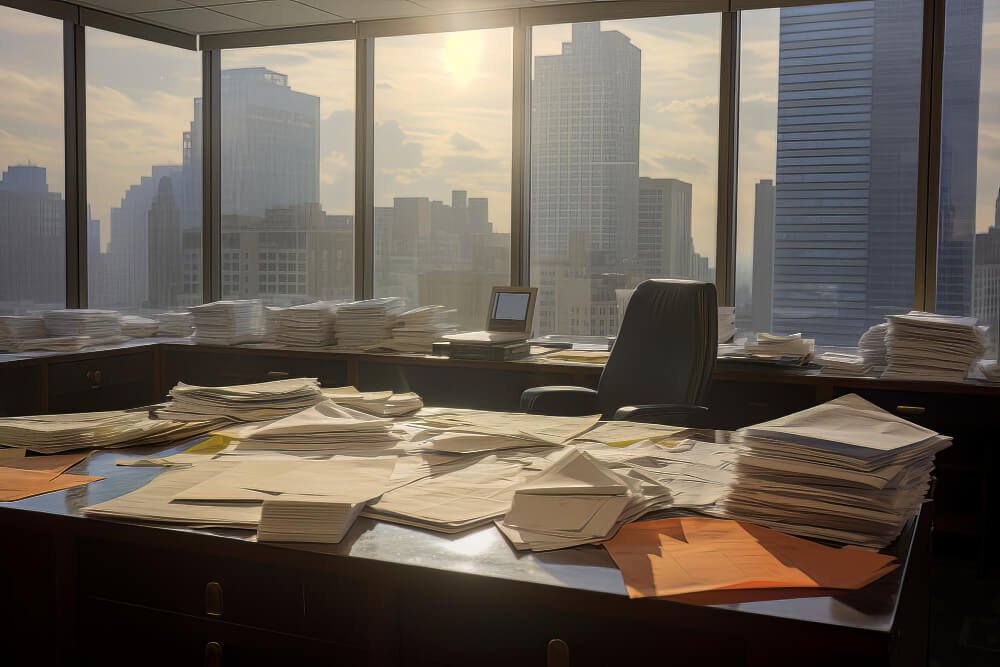

I manage fifty people. Run meetings about strategic initiatives. Make decisions about millions in revenue. Review performance evaluations. Pretend my life isn’t imploding.

Last night, I sat on the floor of my empty apartment eating cereal for dinner at 9 PM, scrolling through videos of my kids from when they lived with me every day instead of every other weekend. This morning, I led a quarterly planning session, projecting confidence about futures I can’t even imagine for myself.

Nobody asks how I’m doing. Not really. There’s the obligatory “How are you holding up?” when the divorce news first circulated, always asked in passing, in hallways, where the only acceptable answer is “Fine, thanks.” But there are no follow-ups. No checking in. No concerned texts at 10 PM asking if I need anything. No casseroles. No support groups. No acknowledgment that I might be drowning.

I’m a divorced dad. Society has already decided my story: I probably cheated. Or was emotionally unavailable. Or prioritized work. Or failed in some fundamental way that justified my family’s destruction. The assumption is that I’m either the villain or, at best, emotionally incapable of feeling the loss the way a mother would.

Here’s what I actually am: A man who went from tucking three kids in every night to seeing them four days a month, pretending that’s enough, pretending I’m not dying from the absence of daily chaos, homework arguments, morning rushes, bedtime stories, Saturday pancakes, and the thousand small moments that made me a father instead of a visitor.

The Myth of Male Resilience

Society has decided men handle divorce differently. We’re supposed to be relieved by freedom. Excited about bachelor life. Already dating younger women. Grateful to escape the “ball and chain.” Working late because we don’t have to rush home. Living our best lives.

Here’s my best life:

- A one-bedroom apartment that smells like fresh paint and failure

- Every other weekend marked on a calendar like scheduled grief

- Fifty hours a week performing leadership while broken

- Texts from my kids that get shorter each week

- Watching my replacement father figure emerge on social media

- Eating standing over the sink because tables are for families

- Silence so complete I leave the TV on for company

Men are supposed to bounce back. Get back out there. Focus on work. Hit the gym. Download dating apps. Move on. We’re not supposed to need help, seek therapy, join support groups, admit devastation. We’re definitely not supposed to cry in our cars after drop-off, sleep in kids’ beds when they’re gone, or keep their dirty soccer uniforms unwashed because they smell like before.

The assumption that men don’t grieve the destruction of daily fatherhood is perhaps the cruelest myth. We’re expected to be grateful for “breaks” from parenting. To enjoy our “freedom.” To appreciate the “simplicity” of part-time responsibility. As if any real father wants a break from his children. As if freedom from bedtime battles feels like anything other than exile. As if simplicity isn’t just another word for emptiness.

Reflection Check-In #1

What aspect of divorced fatherhood cuts deepest today?

⬜ A) The empty mornings without their chaos and noise

The silence isn’t peaceful, it’s suffocating. Consider morning phone calls or texts to maintain connection

⬜ B) Missing the mundane daily moments – homework, dinner, baths

These weren’t chores; they were fatherhood. The mundane was actually sacred. Honor that loss

⬜ C) Becoming a visitor in my children’s lives instead of a constant

You’re still their father, even part-time. Make your limited time count without trying to be Disney Dad

⬜ D) Watching another man step into my daily role

Your children have only one father. No one can replace your unique relationship, only supplement it

⬜ E) The assumption that I’m fine because I’m male

Your grief is real. Your pain is valid. Find at least one person who understands this

⬜ F) Performing stability at work while falling apart inside

The mask is exhausting. Consider whether one trusted colleague could handle your truth

⬜ G) Other:

Whatever cuts deepest deserves recognition, even if society says men don’t feel this pain

The Corner Office Performance

Fifty people report to me. They need leadership, stability, vision, strength. They need someone who can make decisions, project confidence, handle pressure, navigate complexity. They need someone who isn’t googling “how to survive as weekend dad” during lunch breaks or crying in the executive bathroom between meetings.

The performance is exhausting:

- Monday morning leadership meetings while processing Sunday night drop-off

- Strategic planning while your personal life has no strategy

- Counseling employees through their problems while drowning in your own

- Projecting five-year visions when you can’t see past Friday

- Team building exercises while your own team has disbanded

- Preaching work-life balance while having neither

“You seem distracted lately,” my boss mentions. How do I explain that I’m negotiating custody schedules during conference calls? That I’m reviewing divorce papers between performance reviews? That I’m calculating child support while creating departmental budgets? That every notification might be from my lawyer, my ex, or my kids who are slowly forgetting I exist?

The office knows I’m divorced. It was unavoidable – the address change, the emergency contact update, the obvious weight loss, the wedding ring tan line. But knowing and acknowledging are different. There’s an unspoken agreement: I’ll continue performing competence, and they’ll continue pretending I’m not hemorrhaging.

Male colleagues who’ve been through it offer brief, coded support: “It gets easier.” “Focus on work.” “The first year is hell.” Always said in passing, never dwelling, never going deeper. Like prisoners tapping messages through walls, acknowledging shared suffering without actually connecting.

Female colleagues either avoid the topic entirely or offer that specific pity reserved for divorced dads – the assumption that I must have deserved it, failed somehow, probably didn’t help enough with the kids, worked too much, communicated too little. The look that says, “poor kids” not “poor you.”

Weekend Father: The Cruelest Demotion

From daily dad to weekend father. From permanent presence to scheduled visitor. From home to “Dad’s place.” From parenting to “visitation.” The language itself is violence.

Daily fatherhood I lost:

- Morning chaos and negotiating breakfast

- School drop-offs where they forgot their lunch money

- After-school homework battles

- Dinner conversations about nothing and everything

- Bath time for the youngest who still needs help

- Bedtime stories and checking for monsters

- Weekend morning cartoons and lazy Saturdays

- Being there for nightmares, sick days, bad moods

Weekend fatherhood I got:

- Friday pick up where they’re tired and irritable

- Saturday trying too hard to make memories

- Sunday anxiety about Monday’s return

- The pressure to be “fun dad” every second

- Exhaustion from performative parenting

- Drop-off grief that lasts till Wednesday

- Four days of silence punctuated by brief texts

- Missing everything that happens in between

The math is devastating: From 365 days to 104. From 8,760 hours to 2,496. From all their moments to scheduled fragments. From father to part-time.

My youngest (7) asked: “Why can’t you live at home but just sleep at your apartment?” The logic of children who don’t understand that Daddy isn’t choosing this absence. That Daddy would sleep in the garage if it meant breakfast with them every morning. That Daddy’s apartment isn’t freedom – it’s exile.

Reflection Check-In #2

How is the silence affecting you?

⬜ A) The apartment feels like a tomb after the family home’s chaos

The contrast is jarring. Background noise helps – TV, podcasts, music. Silence amplifies grief

⬜ B) Nobody checks in – I could disappear and no one would notice for days

This isolation is dangerous. Force yourself to maintain at least one regular human connection

⬜ C) The kids’ communication is dwindling to logistics and obligations

Keep reaching out even when they don’t respond. Send memes, jokes, observations. Stay present

⬜ D) Work is the only place I speak to adults, and I can’t be real there

The performance exhaustion is real. Consider therapy or one safe friendship outside work

⬜ E) Weekends without the kids are 48-hour voids

Structure helps. Plans, routines, commitments. Unstructured time becomes rumination

⬜ F) Even when people ask how I am, they don’t want the real answer

Most people can’t handle raw truth. Find the one or two who can. You need witnesses

⬜ G) Other:

Male isolation after divorce can be lethal. Whatever you’re feeling in the silence matters

The Apartment: A Museum of Absence

The divorce apartment. Every divorced dad has one. Mine is nice enough – I make good money. But it’s a stage set, not a home. Everything is new because I left them the house, the furniture, the life we built. I got freedom. They got continuity.

The apartment is:

- Too quiet when they’re gone

- Too small when they’re here

- Too white, too beige, too nothing

- Too obviously temporary

- Too much like failure made spatial

Their room here is perfect. Better than at home. New bunk beds. Gaming system. Toys they don’t play with anymore but I bought anyway. Trying to purchase their comfort with objects because I can’t give them permanence. The room is a shrine to part-time fatherhood, immaculate and rarely used.

My room is a mattress on the floor. I haven’t bought a bed frame. Somehow that feels like admitting this is permanent. There are boxes I haven’t unpacked after eight months. Pictures I haven’t hung. As if maintaining temporariness might make this temporary.

The kitchen has four of everything. Four plates. Four bowls. Four forks. One for each of us when they’re here. When they’re gone, I use paper plates. Washing a single dish feels like admitting solitude.

The refrigerator tells the story: Kid food for weekends – nuggets, juice boxes, their favorite yogurt. Bachelor food for weekdays – takeout containers, beer, condiments for food I don’t cook. Two lives that don’t integrate, just alternate.

The Financial Bleeding No One Discusses

I’m a mid-level manager. I make decent money. I’m broke.

The divorce math:

- Child support: 35% of gross income

- Alimony: 20% of what’s left

- Apartment: $2,500 (couldn’t get approved for less with the support obligations)

- Lawyer: $15,000 and counting

- Therapy for kids: Not covered by insurance

- Maintaining two households: Impossible

- Saving for college: Laughable

- Retirement: Destroyed

I’m financing my own exile. Paying for the house I don’t live in. Buying groceries for meals I don’t eat. Covering mortgage on memories I’m not making. Working overtime to afford the life I’m not living.

The assumption is that divorced dads are freed from financial burden. The reality is we’re often funding two lives while living neither. Every dollar spent is a reminder: the family home I maintain but can’t enter, the family life I fund but can’t participate in, the future I’m building for children who are forgetting my daily presence.

Meanwhile, I’m supposed to be grateful. “At least you get breaks from parenting.” “Must be nice having free weekends.” “Think of all the money you’re saving on family vacations.” As if any father calculates the savings of losing daily access to his children. As if freedom feels free when it costs everything.

The Assumption of Guilt

When a marriage ends, society runs a quick calculation: If she left, he must have done something. If he left, he’s abandoning his family. Either way, the divorced dad is guilty until proven innocent, and there’s no court for that trial.

The assumptions:

- I probably cheated (I didn’t)

- I was emotionally unavailable (I tried)

- I prioritized work (I was providing)

- I didn’t help with kids (I did bedtime every night)

- I must have been abusive (Jesus, no)

- I’m probably already dating (Can barely shower)

Nobody asks for my story. The narrative is pre-written: Failed husband. Absent father. Weekend dad. Another statistic. Another mid-life crisis. Another man who couldn’t handle family life. The complexity of how two people grow apart, fail each other, create mutual unhappiness – that doesn’t fit the narrative.

Even my own family assumes blame. My mother: “What did you do?” My father: “Happy wife, happy life – you should have tried harder.” My brother: “She seemed happy at Christmas.” Nobody asks what my happy looked like. Nobody wonders if maybe I was drowning too. Nobody considers that sometimes marriages die from two people’s joint failure, not one person’s singular crime.

Reflection Check-In #3

What support do you desperately need but can’t ask for?

⬜ A) Someone to check on me without me having to reach out first

Men aren’t taught to ask for help. One friend who texts first could save your life

⬜ B) Permission to not be okay while leading others

You can be competent at work and devastated in life. Both can be true

⬜ C) Other divorced dads who actually talk about the pain

They exist but hide like you do. Online communities might be safer than in-person initially

⬜ D) Help with the apartment feeling like a home

You deserve comfort even in transition. One small improvement per week adds up

⬜ E) Strategies for maintaining connection with withdrawing kids

This is specialized knowledge. Counselors who work with divorced dads have practical tools

⬜ F) Financial planning that acknowledges the hemorrhaging

You need specialized help. Regular advisors don’t understand divorce economics

⬜ G) Other:

Whatever you need but can’t voice is probably what you need most

The Kids: Watching Them Drift While Drowning

They’re angry. They have every right to be. Their life exploded too.

My oldest (14) has become monosyllabic. Texts back “k” to everything. Spends weekends here on his phone, earbuds in, present but absent. He’s punishing me for breaking his world. I take it because at least he’s here, even if he’s not really here.

My daughter (11) is trying to parent me. Makes sure I have groceries. Asks if I’m eating. Hugs me longer at pickup like she’s checking if I’m solid. She shouldn’t have to wonder if Dad’s okay. But she sees what nobody else bothers to notice – the weight loss, the dark circles, the apartment that looks like a hotel.

My youngest (7) is confused. Keeps asking when I’m coming home. Still sets a place for me at their dinner table. Tells his friends his dad is “working” when asked why I don’t live there. He’s protecting my reputation or maybe his own inability to accept this permanence.

The distance is increasing:

- Shorter texts

- Rushed phone calls

- “I forgot” about our scheduled FaceTime

- Friends become more important than Dad weekends

- Activities scheduled during my time

- The slow fade of children moving on

I’m becoming a stranger to my own children. Missing their daily evolution. Getting updates instead of experiencing. Hearing about their lives instead of living them. The teacher conferences I miss. The games scheduled on her week. The friend dramas I hear about later, filtered through distance and time.

Their mother isn’t villainizing me (thank God), but she doesn’t have to. The absence does that work. Every day I’m not there is a day someone else might be. Every bedtime I miss is evidence of priority. Every morning I’m not making breakfast is proof of abandonment, even if it’s court-ordered absence.

Where Men Go to Fall Apart: Nowhere

Women have support systems. They have friends who rally. Wine nights where they process. Book clubs that become therapy. Social media groups for divorced moms. Yoga classes where they cry and are held. An entire infrastructure of feminine grief support.

Men have:

- The gym (don’t talk, just lift)

- The bar (don’t talk, just drink)

- Work (don’t talk, just produce)

- Dating apps (don’t talk, just perform recovery)

- Video games (don’t talk, just escape)

- Nobody. Nowhere. Nothing.

I tried one men’s divorce support group. Six guys sitting in a circle, everyone performing stoic acceptance. “It is what it is.” “Just gotta move forward.” “Focus on what you can control.” Nobody actually saying: “I’m dying. I can’t breathe. I don’t know how to do this. I miss my kids so much I physically ache. I’m afraid I’m disappearing from their lives. I’m terrified of being alone. I cry every Sunday night. Help.”

Male friendship doesn’t include emotional excavation. My best friend of twenty years said, “That sucks, man. Let me know if you need anything,” and never asked again. Not because he doesn’t care, but because that’s the contract – we acknowledge pain without examining it. We offer support without specifics. We stand near each other’s grief without entering it.

The loneliness is literally killing us. Male suicide rates spike after divorce. Not because we’re inherently weaker, but because we’re systematically isolated. No one checks. No one asks. No one assumes we need help. We’re supposed to be strong, stoic, stable. We’re definitely not supposed to admit we’re scared, sad, lost, lonely, desperate for someone to give a damn about our pain.

The Replacement Father Fear

He’s already there. The new boyfriend. The “friend” who’s helping around the house. The guy who’s at soccer practice on her weeks. The man filling the daily space I used to occupy.

He’s not evil. He might even be decent. But he’s there and I’m here, and my kids are calling him by his first name with a familiarity that took me years to build and him months to inherit. He’s helping with homework I should be checking. Making breakfast I should be cooking. Teaching them to throw a curve ball I perfected in college specifically to pass on to my son.

The social media photos are torture:

- Family dinners I’m not at

- Weekend trips I didn’t know about

- Holiday moments that were supposed to be mine

- My youngest on his shoulders at the fair

- All of them laughing at something I’ll never know

I’m being edited out of my own family photo. Replaced by someone who gets to be the daily dad while I’m the weekend visitor. Someone who didn’t change their diapers but gets their daily presence. Someone who doesn’t love them like I do but gets to act like he does.

The fear: That my kids will prefer the convenience of a full-time father figure to the inconvenience of a part-time real father. That every other weekend isn’t enough to compete with every day. That love requires proximity and I’ve been proximitized out of relevance.

Reflection Check-In #4

What’s keeping you alive right now?

⬜ A) The kids need me, even if they don’t know it yet

They do need you. Your presence matters even when it feels insufficient

⬜ B) Work provides structure when everything else is chaos

Sometimes routine is the only thing between us and complete collapse. That’s okay

⬜ C) The possibility this gets easier eventually

Other divorced dads say year two is better. Hold onto that hope

⬜ D) Spite – proving I’m not the failure they assume

Sometimes anger is what keeps us upright. Use whatever fuel works

⬜ E) The moments when the kids still need their dad

Those glimpses of connection are real. They’re worth surviving for

⬜ F) I don’t know, I’m just still here

Sometimes continuing is its own accomplishment. That’s enough for today

⬜ G) Other:

Whatever’s keeping you breathing matters, even if it seems small

Year Two: When the Adrenaline Stops

Everyone warns about the first year. The lawyers, the moving, the court dates, the paperwork. The first holidays split. The first birthday missed. The first Father’s Day as a visitor. But the first year has momentum. Crisis energy. Things to do. Battles to fight.

Year two is when the permanence settles. The apartment is still an apartment. The every-other-weekend is routine. The kids have adapted. The world has moved on. Except you’re still in the crater, now with the understanding that this is your actual life, not a temporary crisis.

Year two revelations:

- This loneliness is permanent

- The kids are building lives without you

- The financial bleeding never stops

- Dating feels impossible and pointless

- The replacement dad is settling in

- Work is just work, not salvation

- Nobody’s checking on you anymore

- This is your actual life

The suicidal ideation isn’t dramatic. It’s logical. A spreadsheet calculation: Kids get my life insurance. Ex gets the house free and clear. They’re young enough to barely remember me. He’s already there to raise them. I’m worth more dead than alive and definitely more dead than weekend alive. The thought is so reasonable it’s terrifying.

But then: My son texts “love you dad” randomly on a Tuesday. My daughter asks to stay an extra night. My youngest runs to me at pickup like I’m returning from war. These tiny moments of still-mattering become life rafts in an ocean of irrelevance.

The Permission Nobody Gives Divorced Dads

You’re allowed to be destroyed by this. You’re allowed to grieve as hard as any mother would. You’re allowed to admit that weekend fatherhood is a devastating demotion from daily dad. You’re allowed to be angry, sad, lost, lonely, terrified. You’re allowed to not be okay while everyone assumes you’re fine.

You’re allowed to mourn:

- The daily presence you lost

- The bedtimes you’ll never do again

- The morning chaos you’d give anything to have back

- The family unit that’s permanently fractured

- The future you planned that’s dead

- The identity that’s gone

- The loneliness that’s suffocating

- The financial destruction

- The assumption of guilt

- The absence of support

You’re also allowed to admit if there’s relief mixed in. If the marriage was killing you too. If some mornings the silence is peaceful not painful. If not fighting is worth the emptiness. If you’re grieving the idea more than the reality. Complexity is allowed.

Nobody checks on divorced dads. Nobody brings us casseroles or asks how we’re really doing or creates support groups or acknowledges our pain. We’re supposed to be strong, stoic, stable, fine. We’re supposed to work harder, date quickly, move on, man up.

But here’s the truth: Weekend fatherhood is a special kind of hell. Managing teams while falling apart is exhausting. The silence of the apartment is deafening. The drift from your children is terrifying. The replacement of your daily presence is agony. The loneliness might actually kill you.

You’re not crazy for grieving this hard. You’re not weak for needing support you’ll never get. You’re not failing by struggling to breathe. You’re a father ripped from daily fatherhood, a man processing loss without support, a human being treated like you’re invulnerable when you’re hemorrhaging.

Some of us survive this. Build something different if not better. Maintain connection despite distance. Find ways to matter in limited time. Create new versions of fatherhood that work within constraints. But survival isn’t guaranteed and it isn’t easy and it sure as hell isn’t the “freedom” everyone assumes we wanted.

The kids still need you, even if the world doesn’t recognize your pain. Even if nobody checks. Even if you’re alone in that apartment eating cereal for dinner, scrolling through photos of when you were a daily dad. You still matter. Your presence, even limited, even imperfect, even every other weekend, still matters.

Nobody checks on divorced dads. But we’re still here. Still showing up. Still leading meetings while broken. Still making pancakes on Saturday mornings. Still texting “love you” into the void. Still being fathers, just from farther away.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why don’t men seek therapy or support groups after divorce?

Men are socialized from birth to handle problems alone, especially emotional ones. Seeking help feels like failure, weakness, or admitting we can’t handle our own lives. Most therapists’ offices feel feminine-coded. Support groups feel performative. We’re supposed to be providers and protectors, not patients. Additionally, therapy requires vulnerability we’ve been trained to avoid, emotional literacy we were never taught, and time we don’t have between work and weekend parenting. Many divorced dads do seek therapy eventually, but usually after hitting absolute bottom rather than as prevention. The stigma is real – admitting you need help processing divorce feels like admitting you’ve failed at the one thing men are supposed to handle: being strong.

How do divorced fathers maintain connection with kids who are pulling away?

The drift is real and terrifying. Kids naturally gravitate toward the convenience of the full-time parent. Fighting this requires consistent, patient, non-desperate presence. Text them memes, jokes, observations – not just “how was school?” Send photos of things that remind you of them. Show up to everything you’re allowed to attend, even if they act like they don’t care. Create traditions for your limited time – special breakfast place, movie nights, just-you-two activities. Don’t compete with the other house; create unique value. Most importantly, keep showing up even when they don’t respond. Teenage withdrawal plus divorce can feel like rejection, but your consistent presence matters even when invisible. They’re testing if you’ll disappear. Don’t.

Is it normal for divorced dads to have suicidal thoughts?

Divorced men are 8 times more likely to die by suicide than divorced women. The combination of loss of daily children, financial pressure, social isolation, and absence of support creates a perfect storm. The thoughts often aren’t dramatic – more like logical calculations about life insurance and everyone being better off. This is your brain trying to solve unsolvable pain. These thoughts are common but dangerous. You need one person to tell – therapist, doctor, friend, crisis line. The isolation makes the ideation worse. Most divorced dads report these thoughts peaked around year one or two, then gradually decreased as they built new life patterns. If you’re thinking about it, you’re not alone and you’re not crazy, but you need help immediately.

Why does society assume divorced dads don’t need support?

Cultural mythology says men are less emotional, less attached to children, relieved by freedom from family obligation. We’re seen as providers not nurturers, so the assumption is we’re losing burden not purpose. There’s also moral judgment – if the marriage failed, the man probably caused it. The “deadbeat dad” narrative is so strong that even involved fathers get painted with that brush. Men also participate in this by performing fine-ness, never asking for help, maintaining the strong silent stereotype. The result is a complete absence of support infrastructure for divorced fathers. No casseroles, no checking in, no support groups, no acknowledgment that we’re grieving too.

How do weekend dads handle the empty time between visits?

The void between visits can be unbearable. Structure helps – gym routines, work projects, scheduled activities. Many divorced dads admit to working obsessively just to fill time and avoid the apartment. Some maintain their kids’ presence through photos, videos, and keeping their rooms ready. Others can’t bear reminders and compartmentalize completely. Texting kids during the week helps maintain connection, even when responses are minimal. The key is finding balance between drowning in absence and completely disconnecting. Building adult friendships becomes crucial but feels impossible. Many men report the Sunday night after drop-off as the worst – plan something, anything, for those nights.

End Note

Nobody checks on divorced dads. We’re managing teams while falling apart, becoming weekend visitors to our own children, financing lives we don’t get to live, and doing it all without a single casserole or concerned check-in.

The grief of going from daily dad to every-other-weekend father is a particular devastation that society doesn’t recognize. We’re not freed; we’re exiled. We’re not relieved; we’re gutted. We’re not living our best lives; we’re surviving half-lives in apartments that smell like failure and sound like silence.

But we keep showing up. Keep leading those meetings. Keep making those Saturday pancakes. Keep texting into the void. Keep being fathers from farther away. Not because we’re strong or stoic or stable, but because those kids – even angry, even distant, even every other weekend – are still ours. And we’re still theirs.

Even if nobody checks. Even if nobody cares. Even if we’re dying inside while performing fine outside. We’re still here. Still fathers. Still trying to matter in whatever limited way we can.

That has to be enough. Some days, it almost is.